Love ’em, hate ’em, to be honest, not everyone understands them.

A brief bit of History

Let’s start with some basics. Inco terms or their full title International Commercial Terms were first issued in 1936 by the International Chamber of Commerce. Although a fun fact, the terms FOB has been used since 1812, wonder if that will ever come up on quiz night at the local!!

I know I will have wet your appetite, and I bet most will be off googling INCO and reading Wikipedia.

I will therefore set a challenge, who can find anywhere that defines Incoterms as shipping terms? My respect to anyone that can

Inco terms are international trading terms. They are not legally binding and are more of a guide. They were created to simplify the world of international trade and have a set of common understandings that support a commercial contract (which is legally binding).

Inco terms are a template that will help to define

- what is included in the price, the buyer is willing to pay

- for the items, the seller is willing to sell

- from were

- what is included in the price, the buyer is willing to pay

The were is often overlooked. But for me, a principle behind the Incoterms is what creates the most significant confusion when applied.

Where is the challenge?

First, maybe to return to my earlier point, I have been careful in which words I have used above. However, I must stress that everything relating to shipping, who does what, who pays, and who is responsible is based on the commercial sales/purchase contract.

If it isn’t in this document, you’re out of luck. All actions done by logistics will be based on the commercial contract (not the Inco terms). I know this sounds strange and maybe slightly controversial but….

The Incoterms are, however, a very valuable part of the world of logistics and procuring logistics services. Why not? Most of the hard work has been done, allowing a lot of data to be transferred quickly between the entity requesting the service and the service provider. A crucial part, though, may be overlooked—the where? Which is from whom perspective.

Before everyone starts pointing out that the where is a physical place and that it’s always there, e.g. London is always London. It is essential to look at it from which side of the table you are sitting. Either the buyer or seller. When looking at Logistics services and procuring services, the sellers CIP London cannot be the same as the buyers CIP London.

The Inco terms are based on the seller’s view.

This could mean the buyers may need to buy services based around EXW (pickup point) to DDP (depending on the next leg). The total value to the buyer only comes where they can transfer the intrinsic value into their commercial gain. So maybe sitting at the place the seller sold from is not the same as where the buyer can convert the item into value.

Again to hammer home the point, incoterms are not shipping terms, so they were not built to support the shipping operations. Instead, they were created to have an easier conversation about who is liable? and who pays? And who has the risk?

Or, to put it another way, who needs to pay to manage the risk.

There is risk in the daily life of items being moved worldwide. Risk of damage, theft, loss, theft, delays, theft (I know I keep repeating this, but people are ingenious in taking advantage of an opportunity, both legal and illegal). Incoterms help to create a commercial contract that defines who is liable.

For the eagle eyes out there, I keep using the word liable rather than owner. But, again, I will challenge anyone to find the word owner in the Incoterms.

For example

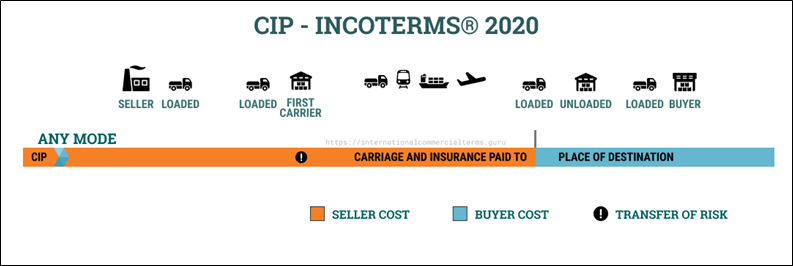

CIF/CIP are probably two of the most common Incoterms used (although sometimes incorrectly)

Or, to be exact, CIF / CIP up to a named destination.

There is nothing that says it needs to be the actual final port. However, I think that may be too much for this conversation.

CIP (Carriage, Insurance, Freight) up to Jebel Ali

- The seller sold an item to the buyer for XXX USD that covers the transport and insurance to Jebel Ali. For those that like to stand out, maybe you are asking where in Jebel Ali?

- The items depart the seller’s warehouse in China and move on the truck to Shanghai port. They are then received at the port and moved through the export process before finally being loaded onto the vessel.

- Technically at this stage, the seller can invoice the client for the goods once they are loaded on the vessel. But, again, this does not define that ownership will have passed. That will be a clause in the commercial contract.

Who is liable for what at this point? If something happens, who is at risk?

Under CIP, the seller pays the insurance (I won’t go too deep down this hole, but insurance is a complex beast that may not cover the liable party adequately; however, let’s assume the right insurance is in place.

If the cargo is lost during transport and an insurance claim is raised, who is the beneficiary, the seller, correct?

Unfortunately, it’s not that straightforward. The buyer is liable for the loss as soon as the seller has raised the invoice. They legally would not be allowed to withhold payment to the seller. Therefore, the seller will submit the claim, but any payout will go to the buyer.

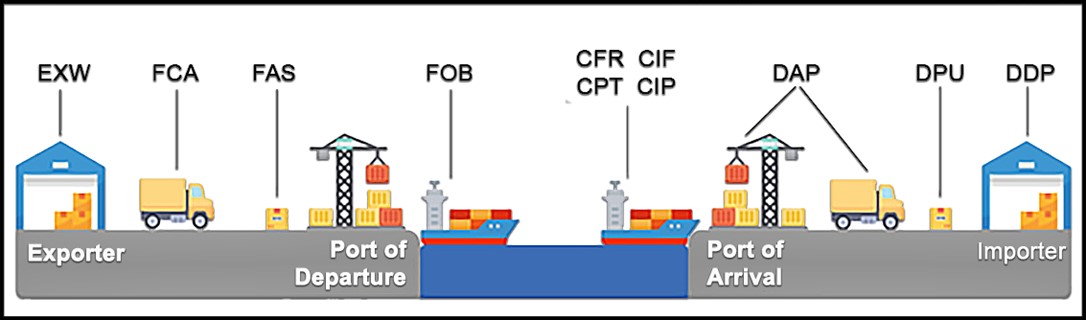

I know there are a lot of diagrams that show the flow pictorially based on incoterms. However, they do not show the depth of the challenge or the risk that is being managed.

Looking at them as purely shipping terms and maybe with the expectation that they are legally binding may catch more people than not.

I could go on into far greater detail, and I am not opposed to the sound of my voice (or, in this case, the typing of my own words); however, I am hoping that maybe I have opened up the challenge a little bit.

The whole point of the incoterms is that they are not the main point. It allowed both parties to know their risk in relation to the risk to the value that the deal will deliver. (simple)

The seller and buyer live in a world of numbers and how much will they generate from the trade. Inco terms (or a customised version) should help them define the details within the transaction and then lock this into a commercial contract that protects (depending on the negotiator’s ability) each party’s interests.

The value

So why do we use them if they have so many limitations?

Because they are so simple, in Logistics, regardless of what you are moving, it is a godsend. When carrying cargo through different countries and cultures based on expectations from different levels, having a snapshot of what is commercially agreed upon will mean that regardless of who you need to talk to will have the same understanding of what needs to be done.

The critical part in this is always the communication, and anything that support this clearly will be better to have than not.

Also, regardless of the level of knowledge globally, they are a common language. As Logistics crosses international language boundaries, this common understanding will help you achieve more together.

And finally, it is because of these limitations that make them so powerful (hear me out); they are at heart a template which, because they are not rigid, allows them to be moulded easily into what you need. As long as the contract supports the terms of the deal and gives clarity where necessary, then this freedom to use what you need from the Inco terms is a powerful tool.

Final thoughts

Maybe it’s time to close this chapter; we all need to move on with our lives. But, I hope I have given a clearer picture of Inco terms through this tornado of information. The potential challenges and maybe why they are not fully understood.

The simplification may be part of the problem. Three letters are as simple as you will get, but they may have created a false sense of confidence in international trade and logistics.

When used correctly, they can protect both parties against damaging their growth. When misused, they add more confusion to what is already a challenging journey.

When used to their full potential, they can impact all levels of an organisation. Whilst opening up so many opportunities for your customers.